Author’s search in South America for the shamans’ plant hallucinogenic yagé and use of apomorphine to control his addiction leads neurologist to call for clinical trials

Author’s search in South America for the shamans’ plant hallucinogenic yagé and use of apomorphine to control his addiction leads neurologist to call for clinical trials

Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and motor neurone disease are the perennial neuro-degenerative afflictions which remind an ageing population that the human brain is still the final frontier of modern medicine.

Now, more than ever, the conundrum of the brain is a profound and fascinating mystery that is inspiring a new generation of graduate neuroscientists and attracting glossy funding for state-of-the-art research. But some of the advances in developing, for example, a cure for Parkinson’s are not hi-tech and have come via unlikely, even exotic, routes. Consider, for instance, the strange tale of Williams Burroughs, “the dead man’s vine” and the British medical establishment.

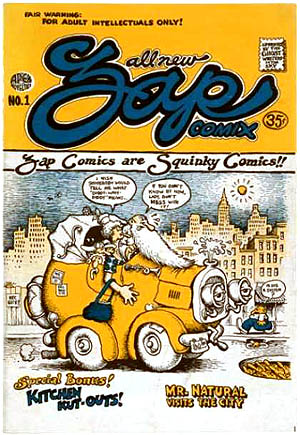

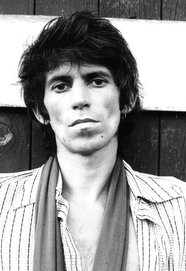

In 1953 the celebrated author of

The Naked Lunch, a countercultural guru and lifelong junkie whose centenary is celebrated this year, travelled to South America on a quest for “the liana [vine] of the dead”, the plant source of ayahuasca, also known as yagé, a natural drug whose hallucinogenic properties, used by shamans, had long been known to European explorers. “All agree,” wrote one, “in the account of their sensations under its effects – alterations of cold and heat, fear and boldness, everything joyous and magnificent.”

Burroughs’s quest for “the final fix” was occasionally nerve-racking. After one infusion of yagé, he told his friend, the poet Allen Ginsberg: “I was completely delirious for four hours. The old bastard who prepared this potion specialises in poisoning gringos.”

The trip accelerated Burroughs’s acute drug dependence. In 1956, conscious that he might otherwise die, he went to London to be treated with apomorphine, a non-narcotic derivative of morphine, by Dr John Dent, a medical maverick and coincidentally the secretary of the British Society for the Study of Addiction.

Dent, who had begun his career in 1918 treating drunks around King’s Cross in London, had pioneered the use of apomorphine as a cure for alcoholism, reporting his findings in the

British Journal of Inebriety in 1931. Acting on an inspired hunch, Dent applied his treatment to the drug-addicted Burroughs, who reported extraordinary results. “Apomorphine,” he wrote later, “acts on the back brain to normalise the bloodstream in such a way that the enzyme system of addiction is destroyed.”

Burroughs, a languid American beanpole with thin lips and pale blue eyes, attributed his international literary success to Dent’s lifesaving treatment. “At the time I took the apomorphine cure,” he said, “I had no claims to call myself a writer and my creativity was limited to filling a hypodermic. The entire body of work on which my present reputation is based was produced after the apomorphine treatment, and would never have been produced if I had not taken the cure and stayed off junk.”

Soon after Burroughs completed his treatment, Dent’s hunch about apomorphine’s remarkable effect on the addict’s brain was scientifically confirmed. But, perhaps because Dent was an outsider, with many in the medical hierarchy opposed to his radical-empiricist methods, his discovery was never fully adopted as a routine cure for addiction.

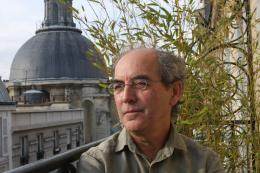

There was, however, a new generation of young, anti-establishment, counter-cultural neurologists coming up through the profession. One of these, a young medical student named Andrew Lees, just happened to be a Burroughs aficionado and had become fascinated by the role of apomorphine in curbing the brain’s propensity to addiction.

Today Lees is an internationally renowned professor of neurology at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, the author of

Alzheimer’s, the Silent Plague (Penguin), and one of Britain’s leading experts in the treatment of both Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s.

In the 1970s, inspired by Dent and Burroughs, Lees and some colleagues began to experiment with ayahuasca, also exploring the use of apomorphine in neurology, especially in the treatment of Parkinson’s.

“Apomorphine,” Lees told the

Observer last week, “is free from narcotic effects and works on the brain by opening the dopamine receptor lock. Burroughs spoke about how it led to enhanced perspective and increased libido.”

At first Lees pioneered his work through self-experimentation. “It was with some trepidation,” he reports, “that I injected myself with 1mg of apomorphine” as the prelude to a fuller clinical investigation.

Later, trials Lees conducted at the Middlesex hospital showed that continuous infusions of apomorphine dramatically alleviated unwanted “switch-offs” (the process whereby patients on long-term L-Dopa treatment suddenly lose the beneficial effects of their medication). As a result, apomorphine became licensed for routine treatment of late-stage Parkinson’s.

Today, however, Lees believes there is an urgent need for more clinical trials: “Drugs like apomorphine should be reinvestigated as an alternative to buprenorphine and methadone in heroin addiction.”

A persistent side-effect of L-Dopa (a naturally occurring amino acid derived from beans) in the treatment of Parkinson’s is its tendency, in a minority of cases, to sponsor addiction with highly disturbing symptoms (binge-eating, obsessive sexual fantasies, reckless gambling, hallucinations and even cross-dressing).

To counter such side-effects, Lees has returned to Burroughs’s accounts of his apomorphine use and says he has found Burroughs’s writing “highly instructive”. Burroughs, for instance, denounces the “vested interests” of the pharmaceutical industry for spending “billions [of dollars] on tranquillisers of dubious value, but not 10 cents for a drug [apomorphine] that has unlimited potential, not only in treating addiction, but in handling the whole problem of anxiety”.

But there is a problem. Where Lees in the 1970s could freely self-experiment at his own risk, new rules and procedures now inhibit this avenue of research. “There’s an urgent need for fresh trials,” says Lees, “in the use of apomorphine for dealing with addiction, but we are up against punitive and draconian legislation. The heroic era of neuropharmacological research has now vanished.”

Lees goes on: “The notion of the investigator as the most ethical first volunteer in clinical trials is now increasingly denigrated by some lawyers and editors of medical journals. Some neuroscientists are being driven underground here.”

Partly from these inhibitions, meanwhile, the use of apomorphine has fallen out of favour. Under-recognised and under-used, the drug that saved Burroughs has become just a curiosity of avant-garde literary life when it could, potentially, become a weapon in the long battle to ameliorate the torments of Britain’s Parkinson’s sufferers.

As Lees says: “Apomorphine has never been fully tested in the way Burroughs advocated.”

On apomorphine cure, Dr John Dent’s life and work: Apomorphine Versus Addiction Warwick Sweenay’s site (2014)